The end of the seventeenth century saw a revolution in timekeeping and in the way society perceived, and made use of, the measurement of time. As the eighteenth century progressed the availability and importance of timepieces increased as clocks entered the daily lives of more and more people. Not merely a luxury commodity for the wealthy elite, they were increasingly a necessity for a far larger and more varied sector of society.

The developing time-consciousness and preoccupation with precision that characterised the later seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had origins in various sources. Contemporaries sought greater understanding of the world through reason and observation: the ‘Age of Enlightenment’ or ‘Age of Reason’ saw the rise of experimental science and a pushing forward of the frontiers of mathematics, physics, astronomy, geology and other areas of knowledge.

Precise observation and experiment demanded precision and accuracy in timekeeping. The end of the seventeenth century saw the development of clocks that were accurate enough to be used for serious astronomical observation. In 1676 Thomas Tompion, one the greatest clockmakers of his day, completed two such timepieces – year-going clocks with thirteen-foot pendulums – for the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. The age’s fascination with gadgetry, newness and novelty, and all things mechanical meant that precision timing also had an appeal in itself. During this period technical advances and superb workmanship combined to place England at the forefront of clockmaking, so much so that in 1711, in order to protect the French trade, King Louis XIV banned the importation of English clocks into France.

This scientific revolution also had an impact on private timekeeping. Social attitudes towards punctuality were changing, with a respect for clock time becoming an index of people’s commitment to politeness and civility. Social conventions and relationships were increasingly time-centred with entertainments, concerts, social appointments, auctions and even cooking times for recipes all reflecting the power of the clock. Trade and travel, particularly with the growth of timetabled coach routes across the country, were increasingly regulated by precise timekeeping. Business activities, horse racing and gambling also relied on the ability to not only tell the time but to measure it accurately: it is significant that the first stop watches date from the early eighteenth century.

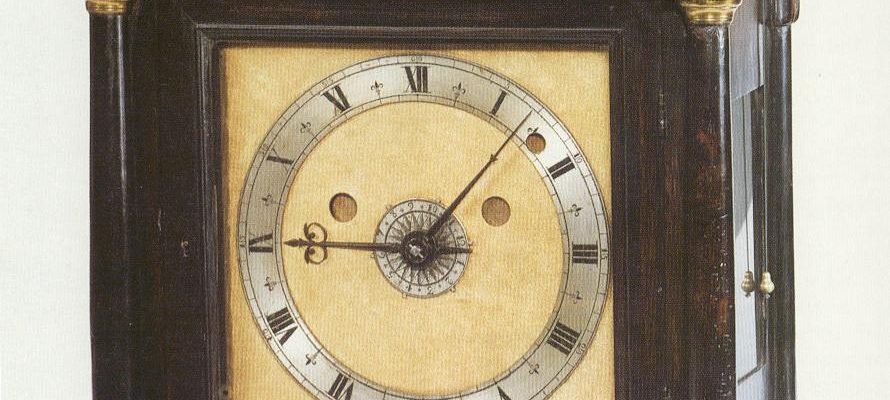

Improvements in technology led to the increased affordability and popularity of the domestic clock. Household inventories from between 1675 and 1725 show that clock ownership rose from a mere 9 per cent to 34 per cent, while in wealthy London households the numbers rose from 34 per cent to 88 per cent. The growing popularity of clocks and watches demonstrated their importance as a focus for Georgian Britain’s consumer society. They were not merely functional but desirable, being invested with aesthetic appeal through decoration and embellishment. The mechanism’s casing, the type of wood, its finishes as well as the individuality of the dial, the engraving and decorative adornments were important elements in the visual appeal of the clock.

In more practical terms, the regulation of time was fundamental to the expansion of business and industry, ensuring that the clock assumed a central place in Britain’s factories. The establishment of time-routines was essential if factories were to be efficient and avoid wastage, ensuring that manufacturers made the best use of time and gained maximum productivity from their workers. The clock that structured and regulated the lives of the wealthy members of polite society was also part of a much broader process of cultural change. From the ballroom to the banking hall, the drawing room to the factory floor, time itself, measured in hours, minutes and even seconds, became the universal arbiter of everyday life. In Britain by the end of the eighteenth century life in all its aspects was subject as never before to the power of the clock.

(From Keeping Time a temporary exhibition at Fairfax House, 5th October-31st December 2012)

Name: Hannah Phillip

Title: Director

Source: Keeping Time (Fairfax House 2013)