The desire to look good and smell good became increasingly linked with the idea of refinement. In particular, the elimination of obnoxious personal odours was considered to be a polite and sociable characteristic. Moreover, certain ‘luxury’ smells could help to identify the wealth of the wearer. The more exotic and rare the ingredients used, the more expensive and exclusive the product. Must from civets was especially valued. Thomas Tyron claimed in 1700 that ‘it was the dearest of Stinks: and if Hog’s Dung was as scarce, it is probable it might be as much in esteem’ (Thomas Tyron, Tyron’s Letters: Domestick and Foreign, 1700).

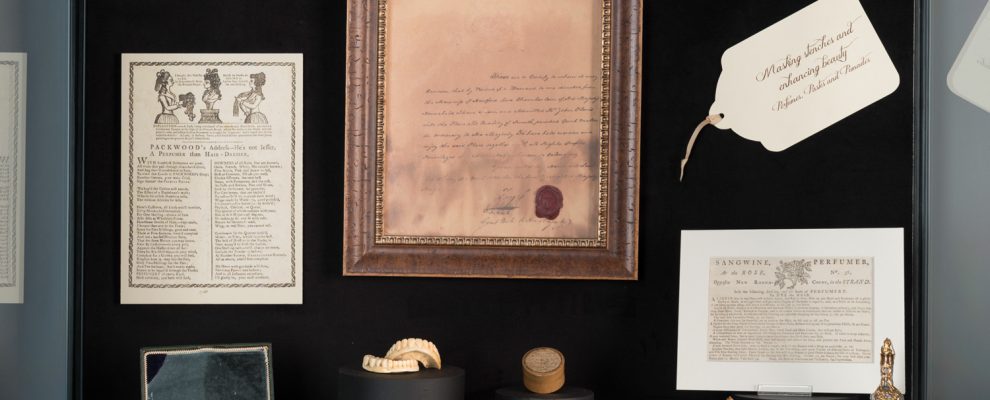

Perfumers in the eighteenth century sold a range of fashionable ‘hygiene’ products. In addition to scented waters, customers could also purchase soap (newly formulated in 1780 by Andrew Pears), combs, powders, and pomades for the hair, as well as tongue scrapers, toothbrushes and toothpaste, reflecting the new obsessions with oral hygiene.

The selling and purchasing of cosmetics was not without its critics in eighteenth-century Britain – critics who associated the painting of faces with ‘Frenchness’. Cosmetics were implicated in female ‘deceit’, and hid true, natural faces from sight. As William Cowper argued

This anxiety to be not merely red or white which is all they aim for in France, but to be thought very beautifull, and much more beautifull than nature has made them, is a symptom not very favourable to the idea that we would wish to entertain of the chastity, purity and modesty of our Countrywomen.

(Letter from William Cowper to Rev. William Unwin, May 3, 1784)

Perfumers were implicated in this deception along with women. The prospect of buying and selling beauty in order to attract male admirers proved particularly problematic for some critics:

That lip, that cheek, by man was never known;

Those favours you bestow are not your own:

Henceforth such kisses I’ll defy like thee,

Which Warren sells to you, and you to me

(London Chroncile, London, Oct 14-16 1773)

Warren (a London perfumer), it is implied, sells a woman the mask (which she adorns in secret) in order to attract an admirer. This commerce of deception was wholly incompatible with the English feminine ideals of simplicity, modesty and domesticity and the mask is the antithesis of the natural English face. Advertisements also reveal that there was an understanding between the female consumer and male perfumer; a secretive relationship that conspired to deceive and seduce Englishmen. A frequent theme in advertisements is that the cosmetic – be it rouge or white – will not be discovered by observers: ‘Its beauties consist in resembling Nature in so great a degree, as to render it totally out of the power of the nicest observer to distinguish the difference’’; ‘French Rouge, and Pearl Powder, in great perfection, neither of which will rub of’; ‘the effect of these Cosmetics are not to be distinguished by the nicest observer.’ (World, London Sat Jan 12 1793; Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, London, Fri Dec 10 1773; Morning Post and Daily Advertiser, London Fri May 24 1776.)

Perfumers in the period also offered grooming services. Packwood of Gracechurch Street, London, was at pains to stress that he was not ‘lesser a Perfumer than a Hair-Dresser’. The fashion, especially from the 1770s, for ladies hairstyles to be raised into substantial headdresses and for men to wear powdered wigs, provided a ready market for the ‘handsome braids of hair’, ‘ringlets’, ‘puffs and rollers, pins and slides’ sold by perfumers such as Packwood. The experience of having one’s hair coiffured was humorously described by Fanny Burney in her novel Evelina (1778):

I have just had my hair dressed. You can’t think how oddly my head feels; full of powder and black pins, and a great cushion on the top of it. I believe you would hardly know me, for my face looks quite different to what it did before my hair was dressed. When I shall be able to make use of a comb for myself I cannot tell; for my hair is so much entangled, frizzled they call it, that I fear it will be very difficult.

Barber’s shops, like other polite retailers at the time, offered more than just grooming services. Historians have shown that they were a space for male pleasure offering society, music, news and the opportunity to purchase items like tobacco. Historian Susan Vincent has noted that wigs, for men, were a sign of masculinity and style, and became associated with high-ranking professions such as the law, medicine, and the church.

Further reading:

Hannah Greig, The Beau Monde, Oxford University Press, 2013.

Colin Jones, The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth-Century Paris, Oxford University Press, 2014.

Aileen Ribeiro, Facing Beauty: Painted Women & Cosmetic Art, Yale University Press, 2011.

Susan Vincent, ‘Men’s hair: managing appearances in the long eighteenth century’, in Hannah Greig, Jane Hamlett and Leonie Hannan (eds.), Gender and Material Culture in Britain Since 1600, Palgrave, 2016.