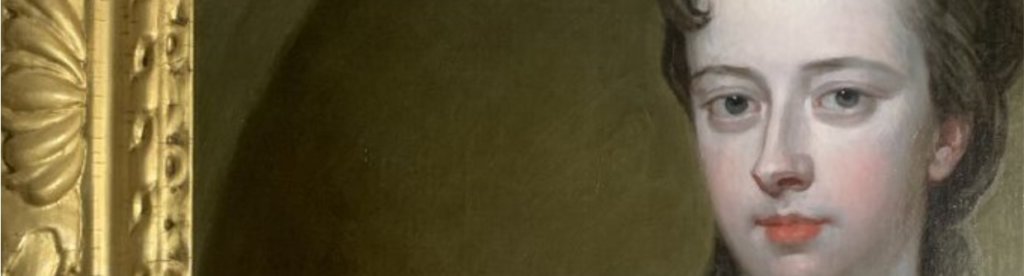

Why Elizabeth, Viscountess Dunbar?

Despite Elizabeth’s marriage to Charles Gregory Fairfax being short – just 6 months November 1720 to April 1721 – and there being no children, she is an integral part of the founding of Fairfax House.

Elizabeth brought with her a vast marriage settlement and the union between her and Charles Gregory was described as the most provident marriage made by Fairfax since the sixteenth century. The money was used to stablise the shaky Fairfax estates and allowed Charles Gregory to later undertake a radical building programme at Gilling Castle. With this capital he was also able to acquire the land that made up the Ampleforth estates and even finance his purchase and remodelling of Fairfax House for his daughter Ann.

Without Elizabeth’s wealth, Fairfax House would not exist as it does today.

Read the full story below…

Who was Elizabeth?

The Hon. Elizabeth Clifford was born in April 1689 in Ugbrooke Park, Chudleigh, Devon. She was the daughter of Hugh Clifford, 2nd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh and Anne Preston, daughter of Sir Thomas Preston, 3rd Baronet. The Cliffords had 15 children, of which Elizabeth was the eldest girl to survive infancy.

Elizabeth was first married to William Constable, 4th Viscount Dunbar, of Burton Constable from 1717 to 1718. The marriage produced no issue. Her second marriage to Charles Gregory Fairfax Esq. (later 9th Viscount of Emley) took place in November 1720, by which time Elizabeth was 31. She unfortunately died just 6 months later in April 1721 in Bath. Elizabeth had been on a visit there to take in the waters and caught smallpox, a disease that would in later years tear apart the Fairfax family. She is buried in Bath Abbey.

Little is known about Elizabeth’s personal life. Her entry in ‘Fairfax of York’ by Gerry Webb – a non-fiction publication about the life of the 9th Viscount – is reduced to just a handful of sentences, all of which sadly do not describe her in a favourable light.

A handful of letters from Cuthbert Constable, nephew of her first husband and inheritor of Burton Constable, survive in the Fairfax Archives at North Yorkshire Record Office. We hope to learn more about Elizabeth as we work on transcribing these letters.

Financial Strife: Elizabeth, the saviour of the Fairfax Estates?

This particular chapter of the story begins with William Fairfax of Lille rather unexpectedly becoming the 8th Viscount of Emley in 1719. His elder brother Charles, married three times with a large family, had been set to inherit but they had all perished before 1713. At the time of his succession William was living in France. At one point he had been an officer in the Imperial service but had spent years drifting between the various garrison towns of the north. The surviving letters in the Fairfax papers from this period suggest more of a hand to mouth existence for this branch, and it seems William was almost overwhelmed by the transition into relative wealth.

The new Viscount of Emley wasted no time plunging into what has been described as ‘an orgy of spending in London’, on coaches of the latest fashion, plate, jewellery and clothing. In mid-1720, before his first year at the helm was out, William had managed to run up outstanding debts totalling £1121.3s., not including the staggering sum of £2335 that he had also recently paid. The years of mismanagement of Gilling coupled with the new Viscount’s exuberant spending meant the estate could not afford to pay these arrears. A crisis was on the horizon, and so William’s son, Charles Gregory, took entire control of the Fairfax finances, bringing on a new land agent to try and improve matters. The Fairfaxes however needed some fast money, and so Charles Gregory entered London society with the intention of finding himself a rich wife, and that is exactly what he did.

On 21 November 1720 Charles Gregory Fairfax married Elizabeth Constable (nee Clifford), Viscountess Dunbar, who brought with her a ‘vast marriage settlement’. As part of the agreement drawn up, Elizabeth was to pay over her original marriage portion of £6,000 to the Fairfax estate. This came from her first marriage to William Constable, 4th Viscount Dunbar and owner of Burton Constable Hall, which had lasted only a mere 8 months before he died in August 1718. William was regarded as a notorious Catholic rake, already with two illegitimate sons, and was 36 years Elizabeth’s senior. They had no issue.

Of the £6,000 Elizabeth brought with her, £5,000 was to form the marriage portion of Mary Fairfax, sister to the 6th Viscount of Emley, a charge laid on the estate by Mary’s father the 5th Viscount. The remaining £1,000, together with £300 a year taken from the £500 a year dower (a widow’s share for life of her late husbands’ estate) from Elizabeth’s first husband and a townhouse in Conduit Street (London) was to go into a trust that her new husband could not touch. Charles Gregory Fairfax was to receive the remaining £200 a year of Elizabeth’s dower.

Elizabeth died unexpectedly just a few short months later, from Smallpox in April 1721, and so all her worldly goods automatically transferred to her husband. Now in want of a wife and heirs, Charles Gregory married his distant cousin Mary Fairfax (mentioned above) in 1722, bringing the £5,000 marriage portion promised to her back into the estates. This second marriage has always been described as a ‘love match’ but it is more likely a shrewd move by Charles Gregory to strengthen the Fairfax coiffeurs.

Charles Gregory Fairfax’s marriage to Elizabeth, Viscountess Dunbar, has been described as the most provident marriage made by a Fairfax since the early sixteenth century. Not including her townhouse or dower, Elizabeth’s vast wealth would have done wonders to stabilise the estate. The Fairfaxes were in no means close to financial ruin, but without this settlement it is probable that more and more land would have had to have been sold to cover the debts run up by the 8th Viscount and earlier mismanagements of the estate.

It is too unlikely that in later years Charles Gregory, by now the 9th Viscount, would have had the funds available to finance such a magnificent townhouse on Castlegate for his only remaining daughter Ann, or indeed purchase the lands that made up the Ampleforth estate and led to the founding of the Abbey. With the money he gained from the marriage settlements Charles Gregory also undertook a radical building programme at Gilling constructing the two wings and transforming the interiors, developing the parkland, lakes, planting trees and establishing the gardens and as well as adding two Temples in the grounds – the stone from which was re-used at Ampleforth Abbey.

Elizabeth’s legacy can therefore not be underestimated, and yet there is still a wealth of information to be explored.